Puppeteers of the World: Ilka Schönbein

Pierwodruk: Lalkarze świata / Puppeteers of the World: Ilka Schönbein, TEATR LALEK 2022, nr 1 (147), ss. 7-12 (wersja polska), ss. 13-18 (English version)

A cycle of portraits of contemporary puppeteers of the world cannot lack Ilka Schönbein (born in 1958 in Darmstadt), a German artist and probably the most original contemporary puppeteer, who for more or less three decades has been present in assorted open and closed theatrical spaces of Europe. Each encounter with her works shocks. The range of created emotions astounds, and the artistic dimension of presentations, the character of used animants, the process of linking them with the body of the actress and the creation of dramatis personae produce admiration.

Upon numerous occasions I posed a question concerning the uniqueness of Ilka Schönbein. My time to time encounters with her theatre made me certain of one thing: she has at her disposal some sort of magic power not limited exclusively to building extraordinary theatrical images or even evoking emotions, which penetrate the audience throughout. Ilka Schönbein touches the most tender chords of the human soul, discloses the most intimate world of artistic creation, moves within the range of metaphysical exultation, and strikes right into the subconscious of the recipient. She surrenders to the characters created onstage.

In the course of several decades Ilka Schönbein has given probably hundreds of spectacles: solo and involving numerous partners, consistently devised by her and most frequently directed or co-directed by her. Often they were conceived with other performers in mind, but always, mainly due to her puppets and created characters, as well as carefully chosen music and partners-vocalists, they were both astonishing and left a deep imprint on our memory.

The source of Ilka Schönbein’s theatrical inspirations is Steinerian eurythmy, literally: “harmonious rhythm”. At the beginning of the twentieth century Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and mystic from the turn of the nineteenth century, and the author of anthroposophy, devised the principles of eurythmy. This art of movement to music, singing, and suitably selected texts deeply penetrates spirituality and is rather widely applied in dance, or, to put it in simpler terms, it translates word and sound in stage performances (artistic eurythmy) into motion. So-called visible speech links a wide scale of emotions, is codified and, at the same time, spontaneous, frees man’s ethereal body, and refers to his spirituality. All those elements are the components of Ilka Schönbein’s spectacles and probably should be analysed within the latter’s context.

For several years Schönbein studied eurythmy in Hamburg, and subsequently practised it for the next decade. Once she acknowledged that she had reached the end of her eurythmic quests, she chose an individual path. She opted for puppets. I immediately knew – she wrote in reflections published in 2000 in the Belgian “Alternatives théâtrales” – that I discovered a language that suits me. I could be simultaneously an author of masks, costumes, and sets, a director, an actress, a person responsible for technical matters, and a dancer! I entered a land of endless opportunities. This is why “limitation” became my motto, making it possible to concentrate on a single path that will lead me deep inside myself. On the way I shall be compelled to abandon many, many things, for the sake of others [1].

Ilka Schönbein belongs to the galaxy of contemporary creators-puppeteers, who knowingly chose puppets having previously shaped other skills and achieved professional experience. They include Hoichi Okamoto, Neville Tranter, and Duda Paiva – to mention several among numerous artists. Schönbein mentioned three such initiation “puppetry” meetings. The first took place during her childhood when she was given a toy-puppet with eyes that close and dressed in a checked skirt (just like hers), and which she named after herself. The second meeting, which occurred several years later, involved a performance given in Paris by a street marionettist displaying a puppet in the part of a virtuoso violinist performing a composition. This remembered encounter with a perfect marionette left an imprint, although at the time it did not have practical consequences. Nonetheless, it obviously became embedded in Ilka Schönbein, because once she ceased working as an adept of eurythmy she presented herself to Albrecht Roser, an acclaimed marionettist of the second half of the twentieth century, and under his guidance spent several years studying the art of puppetry in Stuttgart. Once again, Ilka Schönbein embarked upon a period of study and discoveries. In 1988 she performed in Don Juan, a puppet spectacle directed by Roser, and took part in an international tournée of that production.

Upon numerous occasions Albrecht Roser’s animation mastery was breached by his students. Acceptance of this creative revolt proved Roser’s greatness, as in the case of Frank Soehnle, his first outstanding successor. The Soehnle marionnettes constituted a successive element in the education of Ilka Schönbein. They differed but contained discernible shared elements distant from those characteristic for the puppets of Albrecht Roser: stylistic, classical, demonstrating traditional features of the given character and a specific perfection of form. Frank Soehnle’s puppets, just as those of Ilka Schönbein and, later, Michael Vogel (a representative of a successive generation of the Stuttgart school) are coarse, furrowed, and at times resemble more bare skulls than faces, sometimes with empty eye sockets or downcast eyelids. Their cheeks are inscribed with suffering, pain, sometimes death, and always distinctness. The limbs are elongated and resemble bare bones; hands are considerably enlarged, with disproportionately long fingers. The puppets are made most often out of plastic foam, easy to mould and extraordinarily expressive.

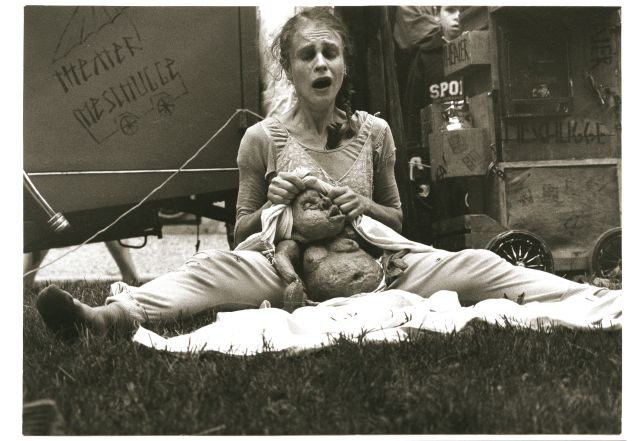

Performances given by Ilka Schönbein often feature (also as puppets) masks, half-masks, variously shaped husks of the head and body parts. Sometimes they assume the form of casts of her face, and upon other occasions – of assorted devised objects. At times, the actress uses them to create distinct characters by holding a mask in her hand comprising as if a neck grafted on her forearm covered with a costume of sorts. Just as often Schönbein builds stage personae by resorting to casings of the torso consisting of a cast of her own, frequently naked body or else outfits her body with elements changing it into another stage character. This juggling between parts of her body, emaciated and displaying ugliness rather than beauty, or casings and objects accentuating the passage of time and inevitable death, become part of the main themes broached in Schönbein’s spectacles. Even the costumes of the actress or her protagonists resemble more sheets of draped matter than classical theatrical garments, although sometimes it possible detect the significant texture of the fabrics, lace, chiffons or tulles.

Ilka Schönbein described the essence of her theatrical style at the beginning of her creative path. Being indebted to Albrecht Roser and Frank Soehnle, she intentionally resigned from using the classical marionette or even its contemporary variant. “I did not hold strings in my hands”, ”I can’t consider any distance” – she admitted. “I let the puppet take possession of my body, my hands, my legs, my face, my belly, buttocks, and my soul. I am left only with my voice, which I have not handed over (yet). [2] “I let the puppet take possession of my body” – this sentence conceals the sense of her oeuvre although it is not easy to describe the latter in words.

In 1992 Ilka Schönbein established her own theatre company, which she named Theater Meschugge. In Yiddish this word denotes madness, frenzy, wildness, and foolishness. Within the context of Schönbein’s works it appears to refer to themes accentuating all sorts of non-normative qualities, deviation, and otherness, and, simultaneously, momentary states of strong emotions, extreme reactions, and behaviour. Numerous characters in her spectacles, especially in Metamorphosen /Metamorphoses, are part of the reality of Jewish ghettoes and the poverty of small towns, although the actress is not of Jewish ancestry. I incessantly experience in her spectacles some sort of fascination with Central European culture, the life of people living there, their poverty, drama, and dreams arising time after time. Quite possibly this captivation with such forms of tension, on the border of life and death, is the reason why her spectacles possess such a fragmentary structure. I have not preserved in my memory some sort of the artist’s linear narration, but episodes, scenes, and particular sequences of her spectacles, in which Schönbein attempts to capture and pause a given moment, stand out. And she succeeds brilliantly.

This structure of spectacles is probably also the outcome of the space, which Schönbein found to her liking: open spaces, small squares, lanes slightly concealed from crowds and noise, but not restricted by stage walls. From the onset of her activity she appears in an entourage of this sort and has enjoyed success for years. At the Mimos Festival in Périgueux (1994) Ilka Schönbein stirred such enthusiasm on the part of the audience that she was presented the main prize awarded by critics, although she appeared in the off current and not the main programme. The prize opened the way to the wide world of puppetry and established closer links with France, where for many years Schönbein performed and directed numerous spectacles most often.

The year 1993 marks the origin of Metamorphoses, a composition involving many episodes created by Schönbein playing the part of a frail beggar, whose partners-puppets emerge from a child’s old pram, an unfolded canopy of an umbrella, or her body, since in accordance with the conception of Theater Meschugge the borderline between the actor’s body and that of the puppet is subjected to constant obliteration. Hence masque de corps, a term used by the artist for describing hybrid creatures to which she lends her body. Puppets thus turn into a prolongation of her person. Not a single word is spoken in this spectacle staged to the accompaniment of klezmer music. Eating an apple offered by a serpent results in a lascivious dance and, finally, birth – this is probably the most beautiful scene of childbirth that I have seen in the theatre, ending with breastfeeding and maternal love, which a moment later is contrasted with disgust caused by the new-born’s first defecation. Infancy and childhood: happiness and nightmare alike, joy and pain, hope and obsession. And successive images upholding this atmosphere of acerbic humour and a decadent vision of the world.

Metamorphoses, functioning chiefly as a street spectacle, also had a stage version. Ilka Schönbein introduced a partner, first played by Thomas Berg (a technician at Meschugge), followed by the French actor Alexandre Haslé, and, finally, by Mô Bunte, a German puppeteer. New versions of the spectacle were constantly devised, including a variation staged as Métamorphose des métamorphoses / Metamorphose of Metamorphoses. The artist changed characters, costumes, puppets, and masks, removed certain scenes and added new ones, thus causing the theatre to take part in a constant process. This state of things appears to be characteristic for her creative path. Ilka Schönbein is never fully satisfied with the achieved result and does not consider the ultimate effect to be perfect. Such an attitude is probably the outcome of working in open space and a feature of the fragmentary construction of her spectacles.

The successive production staged by Ilka Schönbein: Le Roi grenouille/Frog King, after the brothers Grimm (1998), was exceptionally addressed to a young audience and shown in several different versions. The première was co-created with Alexander Haslé, who later – in the restaged version – was replaced by Mô Bunte. The last version (2005) was shown by the team appearing in Winterreise / Winter Journey, presented two years earlier and involving Schönbein (author of the conception, director, maker of masks, puppets, and costumes), Simone Decloedt, Britta Arste, accordion player Rudi Meier, and countertenor singers Christian Ilg or Rainer Philipp Kais, who appeared interchangeably in the part of the narrator. Frog King was inspired by a story about a young Jew who, freezing and on the brink of death, heard the voice of another inmate: ”Dance, dance, if you are a true Hasidic Jew then now you should dance. Dance!” And the young man – Schönbein wrote about her inspirations – pulls his legs out from the soil, his skin sticks to the snow, he dances with bleeding feet and saves his life. Powerful words… If only I could dance in that way! A dance that liberates us, mortals, from the fear of being here for nothing. In Metamorphoses I entered that road, and it is now a question of following it. I still seek a way of extracting characters from my body, creatures that will finally become alive and perhaps on a certain day will teach me why they were born. It seems to me that this is a highly feminine way of creating: women often follow their body, which fulfils them and is the reason why they understand the sense and contents of their existence. [3]

The presence of three actresses in Frog King III multiplied the staged situations, but their essence – forming relations between the puppet and the actor – displays fascinating ingenuity, energy, and constructed emotions. On occasions the puppets, concealed behind a mask or a half-mask, outright grow into the body of the actress, sometimes making it impossible to recognise to whom the hands and legs belong, mixing the torsos of the actresses with the bodies of the animants, and even making use of buttocks to create the ever-changing shape of a toad. After all, the space in which the spectacle takes place is almost empty: it contains an old water tub and a piece of a wide, metal tube.

In 2003 the same team of artists staged Winter Journey, one of Ilka Schönbein’s extraordinary spectacles inspired by music by Franz Schubert and poems by Wilhelm Müller. It is truly difficult to refrain from citing the reflections of the artist telling about her inspirations. During the springtime of her life the woman carries winter in her soul. Her love has been betrayed and winter encases her. Snow covers life at the time of its hatching. A frozen over stream, huddling birds, black branches of leafless trees, pale moonlight, all of Nature shows young life a path from which no one has ever returned. My body and those of my characters will become a shattered mirror of this ailing soul. It is said that love turns its head away: what would happen if the head of my female protagonist was really turned away? It is said that love breaks the heart: what would happen if that gap were to open up on a wave of sand? It is said that pain paralyses and suffering separates the soul from the body… We have all experienced this and live it. I shall request my characters to reveal it. Just as in my previous spectacle this will be question of an approach to themes of elementary significance in a woman’s life: childhood, old age, fear, death. What more? The theme that appears in Metamorphoses – and increasingly strongly permeates my awareness – is the dance of existence: the dance of the embryo in the body of the mother, the dance of ecstatic love , the dance that fills the soul when the body suffers from torment, the dance against death – the dance with death. [4]

All those motifs, subjected to assorted modifications of themes and characters, will return in Ilka Schönbein’s successive realisations. Chair de ma Chair /My Own Flesh and Blood (2006) is a story of reminiscences inspired by the novel: Why Is the Child Cooking in the Polenta by Aglaja Veteranyi. This tale about a circus child evokes relations with the mother, painful loss, the contradictions of fate, a nomadic lifestyle, and rootlessness. Schönbein, this time playing in German and turning her body over to the animants, invited two French actresses: Bénédicte Holvoote and Nathalie Pagnac, to collaborate.

In subsequent years Ilka Schönbein directed and cocreated spectacles performed by other actresses, alongside her own spectacles and the co-productions of Theater Meschugge. These realisations interpreted mainly classical tales. For the Kerstin Wiese theatre she prepared The Wolf and Seven Young Goats /Le Loup et les sept chevreaux, 2006), for Mary Sharp – with whom Ilka Schönbein co-operated upon the occasions of earlier productions – she directed Un froid de Kronos, after Andersen’s The Snow Queen (2006), for Laurie Cannac – the spectacle Hungry like a Wolf, after The Little Riding Hood by Charles Perrault (2008), and Fishtail, inspired by Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (2013). Ricdin-Ricdon, written in 2017, was a Theater Meschugge production and the work of Schönbein, with her puppets and direction, but realised by Pauline Drünert and Alexandra Lupidi. Each time the Schönbein style remained conspicuous, as evidenced by photographs and available fragments of the spectacles, but her absence on stage was felt even intensely.

Schönbein’s own, consecutive première following Chair de ma Chair took place in 2009. This was The Old Lady and the Beast/ La Vieille et la bête. Here Ilka Schönbein’s partner (they cooperate to this day) was Alexandra Lupidi, a multi-instrumentalist of Italian descent, a vocalist with a vast vocal range (also an operatic soloist), and a composer. In the course of the rehearsals the production changed into a duet, and the tale about a little donkey, which initiated the creative process, became a spectacle about the passage of time, a parable about a child dancer who dreams of becoming a great ballerina; a donkey abandoned by its mother, a queen; an old woman who discovers that her sick leg sprouts apple trees… . [5]

In Ilka Schönbein’s productions assorted themes, and sometimes even characters or images that we recall from earlier realisations, recur time and again. She juggles with them, perpetually finding new applications and contexts. This is a source of life. In The Old Lady and the Beast the creative process overlapped with dramatic personal experiences. Her father’s illness and the necessity of interrupting rehearsals in France and returning to Germany introduced Death into the spectacle, a previously unplanned component although very much present in Schönbein’s works. Just as in Tomaszuk’s Medyk Feliks (Feliks the Physician) Schönbein noticed Death – omnipotent, unwavering, and omni-present – standing at the dying Father’s bedhead. And Death was to stay to the end of the spectacle. Death was its “director”, and Father – an “extra-terrestrial consultant”. In this manner, a spectacle about a donkey who played the flute changed into a story about an old lady and a beast.

The characters in The Old Lady and the Beast are hybrid creatures, resulting from the union of masks and prosthetics with Ilka Schönbein’s own flesh. Her characters cannot come to life without distorting her body. For example, the little ballerina is formed by a mask, a prosthetic arm and a tutu on one side, and by the wrist/forearm (forming the puppet’s neck) and the two legs of Ilka Schönbein on the other side. The old lady, an old beast, arises from Ilka Schönbein’s body when the puppeteer puts pants of fur on: her legs become those of a donkey and her hand is gloved with the animal’s head – Anaëlle Impe describes selected scenes. – […] when Death is trapped in a tree, Ilka Schönbein’s body looks as if it is hanging in mid-air (one of her legs is covered with half of a pair of black tights, becoming invisible against the black background, and is replaced visually by a prosthetic leg). In this scene, the puppeteer plays with verticality, which is another characteristic of the grotesque. But the ascension is not infinite: the old lady cannot escape fate and the finitude of human life; she will die as suggested by the fall of the puppet body. [6]

Ilka Schönbein staged several other spectacles together with Alexandra Lupidi: in 2014 – Sinon, je te mange /Or I’ll Eat You, this time inspired by her adaptation of The Wolf and Seven Young Goats, in 2017 – Et bien, danser maintenant/Do You Know What, Then Dance Now, and, finally, in 2021 –Voyage chimère, whose sources are embedded in a story by the brothers Grimm about four musicians from Bremen: a dog, a cat, a rooster, and a donkey. Once again the theme of old age, of demise, the passage of time, and endless longing for retaining those exceptional moments which each of us experienced in his life and whose recollections make it possible to tackle death.

Voyage chimère is yet another concert given by Ilka Schönbein – puppeteer, actor, and interpreter, together with Alexandra Lupidi, responsible for the musical and vocal side and, just like Schönbein, an arch-mistress of her profession.

None of the puppetteers known to me are capable of using their bodies, supplemented by stage costumes and several objects, for building such imagery, meanings, senses, and characters. We always see the actress, but she changes into a full-blooded and necessarily puppet persona. The agility of the body, as if not subjected to gravity, the unexpected and outright unfeasible positions assumed by Schönbein, who at the same time moves in minimal space, create not only enchanting puppet characters but via a number of performed activities, both animation and motion, build a sui generis story about the protagonists. Just as when at the time of death or ultimate danger images from our entire life pass in front of our eyes, so etudes by Ilka Schönbein reveal scenes from assorted stages in the life of the protagonists. Thanks to an extraordinary animation of those forms the actress achieves the effect of a remarkable flow of energy. Motions of the characters become buoyant and joyful, and brilliantly arranged light and suitable positions assumed vis a vis light transform the puppet’s old face into a young one. We observe curious metamorphoses of the dramatis personae, and a second later this entire created world of stage reality vanishes, because it is built by the actress’ almost imperceptible activity. This is certainly the effect of Ilka Schönbein’s fascination with rhythmical dance and a profound knowledge of this technique [7].

In the contemporary world of the theatre Ilka Schönbein appears to be a representative of another planet. Her present-day artistic team, carrying on already for a decade and including apart from Alexandra Lupidi also Suska Kanzler (technician, musician) and Anja Schimanski (lighting and sound technician, but also assistant in many art specialisations), has achieved artistic perfection. And Ilka Schönbein is without doubt the first lady of the present-day world of puppetry.

Photos by Marinette Delanné

[1] Ilka Schönbein, ”J’ai laissé la marionnette prendre possession de mon corps”, ”Alternatives théâtrales”, no. 65-66, 2000, p. 24. [2] Ibidem. Few years later, starting with Winter Journey, puppets took possession also of the voice of the actress. [3] Ilka Schönbein, un théâtre charnel. Photographies Marinette Delanné, Texts Naly Gérard…, Editions de L’Œil, Montreuil 2017, p. 123. [4] Ibidem. [5] Zuzanna Głowacka, Epifanie, ”Teatr” 2012, no. 1. [6] Anaëlle Impe, The Grotesque as a Paradigm of the Puppet Theatre in the 21st Century. Through an analysis of Ilka Schönbein’s show, ‘The Old Lady and the Beast’, in: Dolls and Puppets as Artistic and Cultural Phenomena (19th-21st Centuries), ed. by Kamil Kopania, The Aleksander Zelwerowicz Academy of Dramatic Art in Warsaw, The Department of Puppetry Art in Białystok, Białystok 2016, pp. 172-173. [7] For a review of this spectacle, with elements of its description, see: https://www.marekwaszkiel.pl/2021/09/24/labedzi-spiew/.